Sell me this pen!

Value Selling with the Customer P.A.I.N.S. Method.

Introduction

In the 2013 Martin Scorsese film "The Wolf of Wall Street," a dramatisation based on the memoirs of Jordan Belfort, we witness the rise and fall of a stockbroker whose firm Stratton Oakmont, engaged in rampant corruption, fraud and conning money from the general public into investments that would seldom, if ever, make returns.

Jordan Belfort became wealthy by accumulating high commissions from selling worthless junk stock. Hardly a gold standard case study for a newsletter that preaches the virtues of value-based selling.

But please bear with me.

There's one scene in the film that perfectly explains why most salespeople fail to get results, and actually why most strategic selling and key account management programmes fail. The scene appears twice in the film.

First, Belfort is sitting at dinner with several of his team members, coaching them to sell. They're struggling to understand what he's describing.

Sell me this pen!

Belfort then turns to his favourite salesperson, Brad, and asks him to show them how it's done. Brad takes the pen and looks to Belfort.

"Why don't you do me a favour and write your name on this napkin?" asks Brad.

"I don't have a pen," replies Belfort.

"Exactly – simple supply and demand," retorts Brad.

Hardly value-based selling, but effective. Brad created urgency and a need. The usual approach from most salespeople is to spend time listing out the benefits and features of the pen or the "thing" that they're selling.

Selling fails because there's no understanding or empathy for the customer's needs. There's no appreciation of what they value, and hence might be willing to buy. It happens all the time, from selling a $5 pen to a $500 million power station.

You seek to understand what the customer values first, and then you position your offer as a possible solution to make things better for them. You offer the customer an "Improved Future State."

Bad selling is bad business

When salespeople lead with their agenda rather than the customer's, disengagement becomes inevitable. The moment a prospect senses that you're more interested in hitting your numbers than solving their problems, trust erodes and attention wanes. It becomes painfully obvious that you just want to sell your stuff – that this is your agenda, not theirs.

Here's the thing though: we're not asking you to develop an entirely new product, which would be unreasonable. But adding some simple processes and services to your base products could make all the difference between a sale that commands high value and one where you're forced to compete solely on price. The companies that master this distinction rarely find themselves in bidding wars or having to slash margins to win business.

Consider who you're actually selling to. Is it a board member or the end user? The perception and actual needs shift dramatically, and so must your approach. You pitch differently to someone who's going to use your product or service versus a member of the board. Board members want to see a quantifiable return on investment, clear metrics, and strategic impact. Users want their lives to be made easier, their jobs to be more manageable, and to look good to their colleagues and superiors.

This fundamental misalignment between seller focus and buyer needs creates a cascade of problems. Sales cycles stretch longer than necessary. Proposal after proposal gets rejected or ignored. Even when deals close, they often do so at reduced margins because price becomes the only differentiator when value isn't properly established and communicated.

A wider problem than you might think

I'm a big believer and consumer of the principles of copywriting. And copy is writing that sells.

Let's get one thing straight: If it's not selling something, it's not copy.

Any word or phrase you put in front of your audience sells some form of information at some form of a price to your readers, whether that's their trust, time, effort, attention, clicks, or actual dollars.

This means that all of your copy – your home page, social posts, blogs, landing pages, product descriptions, and mission statement – should always be selling, as copywriter Joanna Wiebe reminds us.

There are many frameworks for copywriting, but the most common is What, So What, And What Next?

What? You describe the problem that the reader or customer is experiencing.

So What? You describe the implication and impact that this has on their business.

What Next? Finally, you describe what you have that can resolve or help them manage the problem.

But most writers, and salespeople, dive straight in with the "What Next" or the features of the thing they're selling, usually because they have large incentives and targets to sell these things.

The issue is clear: if you want to sell, you start by understanding the customer problem, ramping up the pain that this is causing them, and finally providing a possible solution if you can at that stage.

Effective selling takes time, effort, energy, patience and a skillset to engage with multiple stakeholders in the customer business. The big problems and the high value-impact areas typically reside deep in the core of the customer's business.

So... how do you sell that pen?

The heart of many failed selling outcomes – whereby either the sale is lost altogether or the price has to be lowered since that's the only factor that can be negotiated – stems from a poor approach to selling. More specifically, an absence of selling that is truly value-based.

To help address this, I've developed a framework that I call P.A.I.N.S. value-based selling.

Sales teams and key account managers – in fact, anybody who's interacting with customers and stakeholders where they want to secure a better outcome for themselves and the customer – can adopt this model.

The Customer PAINS Value-Selling Cycle

Davies / Value-Matters (2025)

You can see how it's inspired by copywriting, a time-proven approach to selling, and a technique that can be adopted by anybody who's trying to influence or make a sale.

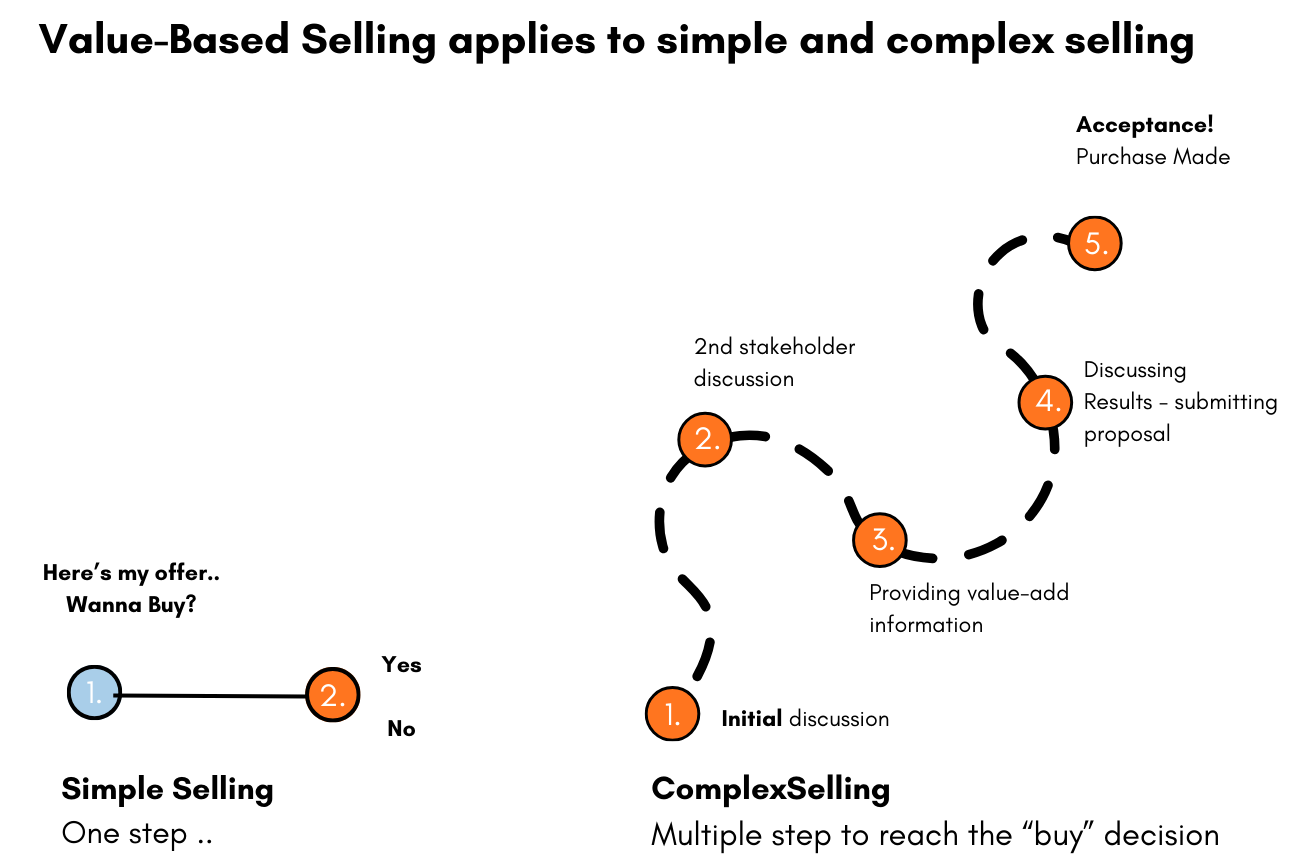

Note: Selling a pen is regarded as a "simple" sale. The customer either buys or walks away at that one transaction, although I have been pondering an Apple iPad pencil priced at £150 for several months.

In B2B selling, the process is usually complex. There will be several "steps" that are taken, as the supplier organisation navigates between various stakeholders to reach a final "buy" decision.

The P.A.I.N.S. model works equally well for simple and complex sales.

The five steps explained...

1. What's your problem?

Identify and frame an issue the customer is facing that you could improve and they would value.

The foundation of value-based selling lies not in your product specifications or service capabilities, but in your deep understanding of what keeps your customer awake at night. This requires doing your homework before you ever walk into that first meeting. Research the customer's industry, understand the macro-economic events affecting their sector, and get familiar with their competitors. Try to establish what sorts of things represent opportunities and threats in their world.

Map out the people in the customer organisation that you need to speak with. This isn't just about identifying the decision-maker, though that's important. You need to understand the ecosystem of influence within their company. Who uses the solution day-to-day? Who measures its success? Who controls the budget? Who has veto power?

Establish a single person who can act as your sponsor. Ask if they can guide and help you meet with key decision makers. This sponsor becomes your internal advocate, someone who understands both your solution and their organisation's politics well enough to help you navigate effectively.

Over several meetings, you'll start to understand what the customer is trying to achieve, and more importantly, the barriers preventing them from reaching those goals. These barriers become your "problem." But here's the crucial part: frame these barriers in terms of their impact on customer value. Don't just identify that their current system is slow. Quantify how that slowness translates into lost productivity, missed opportunities, or frustrated customers.

A manufacturing company might tell you their equipment breaks down frequently. That's a symptom. The problem is that unplanned downtime costs them $50,000 per hour in lost production, damages their reputation with key customers, and forces expensive overtime to catch up on delayed orders.

2. Agitate:

How painful is this problem for the customer?

Calculate the impact that this issue is having on the customer's business. Describe the loss of performance and reputation.

Once you've identified the problem, it's time to help the customer understand its true cost. This isn't about being manipulative or creating false urgency. It's about bringing clarity to pain that often remains hidden or underestimated.

When you have a clear picture of the problem, start to consider its broader impact on the customer's business. Is it preventing them from selling to their customers? Perhaps their slow response times are causing prospects to choose competitors, or their quality issues are triggering penalty clauses in existing contracts.

Is it making them inefficient and costing them money? Calculate the real financial impact. If their manual processes require three extra staff members working at $60,000 per year each, that's $180,000 annually, plus benefits, plus the opportunity cost of what those talented people could be doing instead.

Is it a reputational or risk issue? In today's connected world, operational problems don't stay internal. Late deliveries get discussed in industry forums. Security breaches make headlines. Compliance failures trigger regulatory scrutiny.

Consider other managerial problems the issue creates. Maybe the current situation means their best people spend time on routine tasks instead of strategic initiatives. Perhaps it forces reactive rather than proactive decision-making. Maybe it creates internal friction between departments.

Describe these impacts and quantify them wherever possible. Help the customer see that what might seem like a minor operational hiccup actually represents a significant drain on their business value. The goal isn't to cause panic, but to create a clear, shared understanding of why solving this problem should be a priority.

When you can show a customer that their current situation costs them $500,000 per year in measurable impact, your $150,000 solution doesn't seem like an expense – it looks like a smart investment with a clear return.

3. Indicate:

Could you indicate a better way?

Describe how your offer could improve the customer's future state.

This is where you begin to transition from problem exploration to solution indication. Notice the word "indicate" rather than "present" or "pitch." You're not yet making a formal proposal. Instead, you're helping the customer envision what their world could look like if the problem were resolved.

Start thinking about what you might offer, but frame it in terms of outcomes rather than features. What would the future state look like for the customer if they adopted your solution? Paint a picture of their improved reality. Instead of saying "Our software processes 10,000 transactions per minute," say "Imagine if your team could handle peak demand without system slowdowns, customer complaints, or the stress of wondering whether everything will hold together."

Indicate both the tangible and intangible impacts. The tangible impacts are usually easier to measure: reduced costs, increased revenue, improved efficiency metrics. But don't underestimate the intangible benefits: reduced stress, improved employee morale, enhanced reputation, greater strategic flexibility.

If you need to, speak with different customer stakeholders and decision-makers to understand how your solution would affect various parts of their organisation. The IT team might care about system reliability and security. The operations team focuses on productivity and ease of use. The finance team wants clear return on investment and predictable costs.

You're indicating how you can help and what they need to do to make these improvements happen. This isn't about overwhelming them with technical details or implementation complexity. It's about showing them a pathway to their better future state. Help them understand not just what the destination looks like, but that the journey is achievable.

4. Navigate:

Continue in one of three ways:

SELL now, CONTINUE developing the idea, or STOP and look for other opportunities.

This is where both you and the customer navigate the next step together. Think of this as a collaborative decision point rather than a high-pressure close. You essentially have three possible paths forward, and the key is recognising which one you're on.

The first path is the one every salesperson hopes for: they buy your offer. You draw up the contract and shift to the solution phase. But here's what many salespeople miss – this positive outcome is only possible because you've done the hard work in the previous steps. You've built understanding, quantified value, and created a shared vision of improvement.

The second path is more common and nothing to be discouraged by: they're not sure, but they like the approach. This means you need to work a bit harder on either understanding the problem more deeply or refining your offer. All is not lost, and you should expect this step to be repeated several times in complex B2B sales. Each iteration brings you closer to a solution that truly fits their needs and circumstances.

The third path requires courage and business discipline: you stop. There's no interest from the customer on this occasion, at least not right now. This isn't failure – it's intelligent resource allocation. Look elsewhere for opportunities where your solution creates genuine value and where the customer is ready to act.

Many salespeople struggle with this third option, but it's often the wisest choice. Pursuing unqualified opportunities wastes time and resources that could be invested in more promising prospects. Plus, stopping gracefully today often leads to opportunities tomorrow when the customer's situation changes.

5. Solution:

You have the sale! Now implement the solution and deliver the value you promised.

Making the sale is just the beginning. Now comes the critical phase where you prove that all your value promises weren't just clever selling – they were accurate predictions of what you could deliver.

Put processes in place so that you can measure the impact you're making. Remember, you've made specific promises about improving their situation and providing an improved future state. Your organisation needs to deliver on those promises, and you need systems to track and validate that delivery.

This measurement isn't just about internal accountability. It's about demonstrating value to your customer in ways they can see and share with their colleagues and leadership. If you promised to reduce their processing time by 40%, track and report on those improvements. If you indicated cost savings of $300,000 annually, help them calculate and verify those savings.

Get the customer to acknowledge and sign off on the value delivered. This isn't about legal protection – it's about creating a shared recognition of success that becomes the foundation for future opportunities.

The trust advantage (around and around)

The P.A.I.N.S. model is designed as an iterative "cycle" for good reason. When you deliver what you promise in your solution, something valuable happens for future sales opportunities. The next time you come to this customer, they'll trust you. They should be more open to explaining what their new problems are because they've learned something important: when we ask these people to help us with our problems, they provide solutions that add genuine value to our business.

Always look to maintain "the next sale" if you value and see continued opportunity with the customer. How do you do this? Add value. Add value. Add value.

This doesn't mean constantly trying to sell them more stuff. It means consistently looking for ways to help them improve their business, even when there's no immediate sales opportunity for you. Share industry insights. Make valuable introductions. Provide benchmark data. Offer strategic perspectives based on your work with other clients.

This approach transforms you from a vendor who occasionally sells them something into a trusted advisor who consistently helps them succeed. And trusted advisors get invited into conversations about new challenges and opportunities long before those conversations become formal procurement processes.

Final thoughts

At the end of "The Wolf of Wall Street," Jordan Belfort is seen walking onto a stage, delivering a selling class to a cohort of eager students. He has just been released from a several-year jail sentence.

What is his opening line as he's introduced on stage?

"Sell me this pen."

Of course, fraudulent selling is not to be condoned. Jordan Belfort would be the first to admit that. But good selling, especially value-based selling – that's transformative.

The difference between manipulative selling and value-based selling isn't in the techniques – it's in the intention and the outcome. Manipulative selling creates value for the seller at the expense of the buyer. Value-based selling creates value for both parties through genuine problem-solving and mutual benefit.

The P.A.I.N.S. model gives you a framework for the latter. It helps you approach selling as a collaborative process of problem identification, impact quantification, and solution development. When done well, your customers don't just buy from you – they partner with you to improve their business.

And that's a pen worth selling.

Next steps

If you liked this article or would like to make comments, please get in touch with me.

[email protected]

If you're interested in coaching and training on Value-Based KAM and Offer Development & Innovation for your team, visit our website and get in touch!

|

Coaching Value Matters provides advice, coaching and training support for B2B suppliers. We specialise in Key Account Management, Offer Developmen... www.value-matters.net |

Responses